A History of Whitehall Mansion and its Cemetery

Story and photos provided by Chelsea Mitchell, Director of the Woolworth Library, Stonington Historical Society

The story behind Whitehall Mansion, a historic house that was almost demolished to make way for I-95, is an intriguing tale of the transactional nature of property and the people who saved it.

The Land

In 1630, John Gallup arrived from England aboard the Mary and John. John Gallup, Sr. died in 1650, and by this time, the Hartford Colonial fathers were giving out grants of land for services rendered to the budding country. John Gallup Jr. was given 300 acres of land for his father’s assistance in negotiating with the local native population just south of Reverend Blinman, the new minister, who was awarded 260 acres on the east bank of the Mystic River. It was this plot of land that begins the story of Whitehall Mansion.

John Gallup, Jr. built a house in 1653 on the east bank of Mystic, which stood on the hillside east of Elmgrove Cemetery. He was a very prominent man in colonial affairs; serving as Selectman of Stonington, a representative at Hartford, shipowner, trader, Indian interpreter, and Captain of the First Company of Connecticut forces. During this period, between about 1650 and 1675, thirty to forty thousand English settlers had acquired homes in settlements along the coast and up the length of the Connecticut, Thames, and Mystic Rivers.

Native peoples were also in the area, rapidly being encroached upon by a completely alien group of people. The differences between the indigenous people and the English settlers in culture, religion, ethics, and law concepts were too great to surmount, and by 1675, King Philip’s War broke out. On Sunday, December 19, 1675, Captain John Gallup led his company to the Indian fort at Kingston. This day would later become known as the Great Swamp Fight. He was killed in action and is buried with others in a mass grave near Smith’s Castle at Wickford, where memorial stones honor their memory.

By 1644, Reverend Blinman had sold his land to a neighbor, Thomas Parke. Mr. Park’s forebears in England owned a home in Essex called Whight House. It’s possible that when Thomas Park bought the land from Reverend Blinman, he applied that name to the property, and over time it transformed into Whitehall. When Thomas Parke died in 1644, he donated a parcel of his land to be used as a cemetery by the community. Later deeds by families living on the land established the parcel as “a burying place forever in consideration that the neighbors thereabout may enjoy the burying place as a burying ground forever.” By 1680, the Parke parcel of land had been sold to the Gallup family.

The House

One of Captain John’s sons, William, built a house on the property, and it was on that foundation that the house we call Whitehall was built. Lieutenant William Gallup was married to Sarah Chesebrough of Stonington and six children were born between 1688 and 1701. He, like his father and grandfather, was a prominent man in town, serving as Selectman, representing Stonington in the General Court, and also serving as an Indian interpreter.

The home that William Gallup built on the property was most likely constructed of heavy, hand-hewn timbers, thick walls with some sort of plaster interior, and narrow barred windows which may have had glass panes. In the center of the home was a large stone chimney, wide fireplaces in three large rooms downstairs and maybe four rooms upstairs. The furniture in the house would have been very rough by our modern standards. Most were homemade, and some would have been imported from England. Cooking and eating equipment consisted of brass and iron kettles, pewter and wood plates and mugs, steel table knives, silver and horn spoons, and single-tined forks – indicative of a wealthy family.

William and Sarah lived in the house for a number of years, and when they died, left it to their youngest daughter, Temperance, who sold the homestead and farm in 1760. Four years later, Dr. Dudley Woodbridge acquired the property and built the Whitehall we know today.

Dudley Woodbridge was descended from a long line of ministers, and although he received an education and spent a few years in the ministry, it did not last. He decided to become a doctor, and became a very successful physician, although it appears he did not go to school to learn his craft. He built a tavern that also doubled as a doctor’s office and clinic in the 1750s, and served as the Groton representative in the General Assembly at Hartford various times between 1735 and 1762. In the second half of his life, Dudley Woodbridge gave up the tavern house and acquired the land that held the old Gallup homestead. We do not know what became of the old home because the Whitehall we know now was built on its foundation. It could have burned, but it is also likely that the original structure was torn down to make way for what Dr. Woodbridge would build between 1771 and 1775.

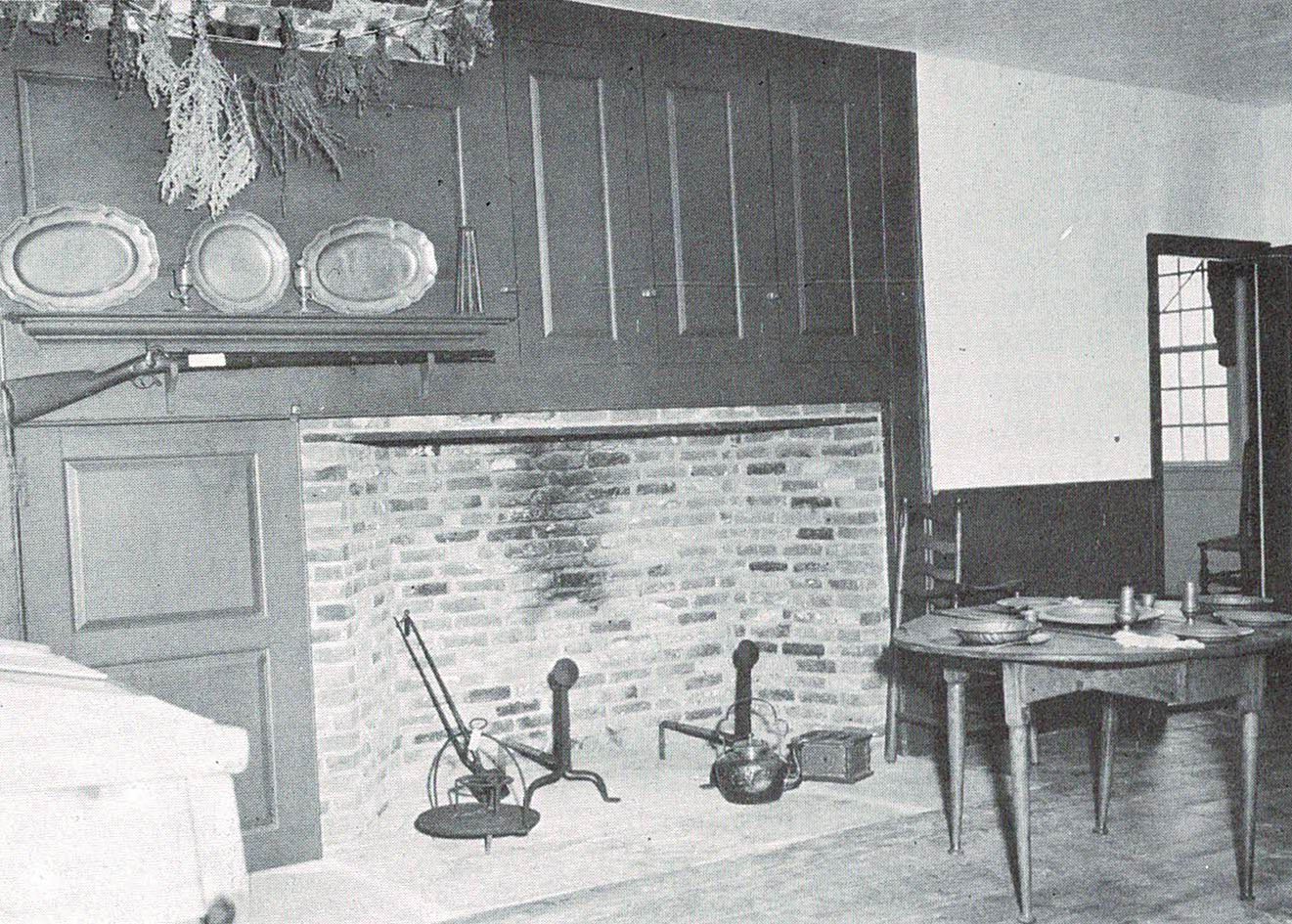

Whitehall Mansion, as designed by Dr. Woodbridge, had 3-foot cedar shingles on the outside, and the foundation was quarried stone built upon a solid ledge forming a half cellar. There was a large fireplace in this basement with a trimmer arch above it, supporting the hearthstone of a fireplace in the room upstairs. On the south side, the basement opened out at ground level through a double door that may have been retained from the older building of William Gallup’s. This separately hinged upper and lower door leads to the speculation that the basement might have served at some time as a store or tavern. The front door of the house faced east, opening upon a hallway with a colonial-style staircase directly ahead against the chimney. To the right and left were the two “front rooms”, both opening to the long “great hall” at the rear of the house. To each side of this great hall were twin small rooms – one a buttery, the other a kitchen washroom.

As is typical in a colonial home, the central chimney was huge, with a kitchen fireplace in the main room including Dutch ovens for baking. Smaller fireplaces were also in each of the two front rooms. Upstairs the layout mirrors the ground floor. Allegedly there was a secret space in the attic floor, accessed by pulling up certain floorboards. This led to speculation and gossip that the house was a station on the underground railroad and another story that claims the secret room had a passage that led to the riverbed. However, when the surrounding area was excavated to build 95, no such passage was found. You can see the edge of the trimmer arch in this picture above the plates. It was used as extra support for the hearthstone on the floor above.

It is important to note certain features in the house that set it apart as far more sophisticated than a typical 18th-century farmhouse. The ceilings on the first and second floors are quite high, as is the gambrel roof. The windows on both floors were 12 over 12, instead of the more common 8 over 12. The chimney is constructed entirely of brick which is unusual; typically a chimney would be made from rough stone. Beneath the cedar shingles, the outer walls are nogged with brick from the foundation to the top floor – an 18th-century equivalent of fiberglass insulation. Turned balusters in the front stairway, woodwork with cornices, and paneled wainscoting in every room contribute to the overall impression of elegance. When originally built, the wooden shingles would have been left natural. Sometime thereafter the house was painted red. However, in the earlier part of the twentieth century, the house was painted white and remained that color for many years, leading many to believe that the name Whitehall was due to the color of the house.

When Doctor Dudley died, he had quite a fortune, but no will. The house and surrounding lands passed to his son, who upon his death some 35 years later, left the house and property to three grand-nephews. Two of them sold the property in 1852 to Joseph Wheeler.

Joseph and his wife Mary Swan had two young daughters when they moved into Whitehall. A third daughter, Julia, was born in the house not long after. Joseph came down with consumption a few years after moving into Whitehall. He attempted to cure himself with a short stint in Florida, but when he did not fully recover, gave up farming after only ten years. Joseph and Mary moved out of Whitehall and into a house in Old Mystic in 1862, and just ten years later, Joseph died.

Joseph and Mary’s second daughter, Louise, had married Samuel H. Bentley, who was also a farmer. After her father’s death, Louise inherited 37 acres and Whitehall from his estate. Louise, Samuel, and their four children moved into Whitehall sometime shortly after 1882 when the estate was settled. Their youngest child, Florence Grace Bentley, was born in Whitehall.

Samuel was a farmer but was also in insurance for a number of years, briefly ran the hotel in Niantic, and served as postmaster in Old Mystic. Louise was a school teacher as her mother had been. After the death of their parents and brother in the early 20th century, the remaining girls enjoyed summers in Whitehall from 1910 until 1960, when Florence Bentley Keach was the sole surviving heir.

Florence Bentley Keach gave Whitehall to the Stonington Historical Society in 1962 in an effort to save the building from being demolished to make way for Interstate 95. Many people and organizations tried to save Whitehall, but to no avail against the forces of the highway! Finally, Ms. Keach offered $15,000 and 5 acres if the Historical Society would take ownership of the home and move it safely out of reach of the interstate.

The Stonington Historical Society carefully restored and staffed the home for thirty years until 1991 when the Society announced it could no longer afford to run the mansion as a museum and decided to close it and sell the property. In 1993, the Historical Society sold the home to Whitehall Mansion partners, with the stipulation that the house be preserved in its original form.

The Cemetery

The land for the Whitehall Yard burial ground was given by Robert Park when he died in 1644. It is the oldest cemetery in Mystic and includes 175 graves. 140 of those graves bear one of the following five family names: Dean (18), Gallup (27), Wheeler (17), Williams (70), and Woodbridge (8). One of the oldest stones in the cemetery is of Thomas Wheeler, who died in 1686, the pioneer of that family.

Also in this cemetery are some graves of formerly enslaved people, like Quash Williams. He preached at Fort Hill Baptist Church in Groton and lies beside his wife, Hannah on the west side of the cemetery. His motto, “walk as well as talk” adorns their stone. There are also memorial stones to Robert Parke, the original owner of the land, as well as Captain John Gallup who was killed in the Great Swamp Fight.

There is also a rarity for colonial cemeteries – an underground vault used on wintry days when the earth was so frozen that graves could not be dug until Spring came. Whitehall Yard also contains the graves of 13 Revolutionary War veterans. In the Gallup family, many of them were present for the burning of New London and were stationed at Fort Griswold. Six of the Gallup boys at Fort Griswold survived, while another 12 died in action. In 1998, the Anna Warner Bailey chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution had a rededication ceremony at the Whitehall yard and installed the refurbished iron gates given in 1903 by a previous DAR chapter.

The headstones in this cemetery are really wonderful examples of the 17th and 18th century stone carving tradition. Twenty-two of the stones are the work of the prominent Manning family, Josiah and his sons Rockwell and Frederick, whose style dominated eastern Connecticut for half a century. Joshua Hempstead, of New London, carved others.